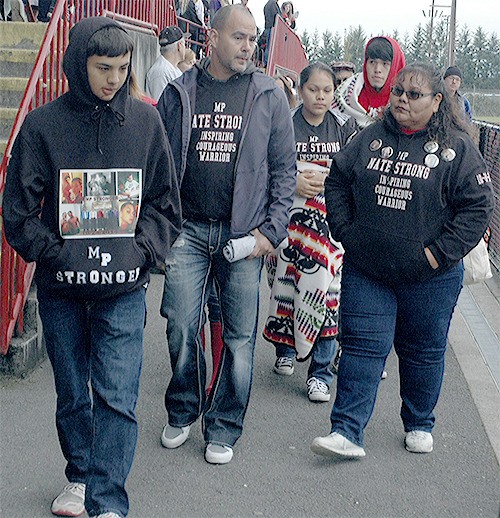

MARYSVILLE — The one-year anniversary of the Marysville-Pilchuck High School shooting was marked with a walk on the stadium’s track Oct. 24, with participants including survivor Nate Hatch.

While school district, city and tribal officials each offered their thoughts on this occasion, those who have worked with the grieving pointed to concrete steps that had been taken toward recovery.

Marysville schools superintendent Becky Berg noted that staff have been trained to recognize signs of mental illness, while Tulalip Tribal Chairman Mel Sheldon Jr. cited the tribal meetings to give a voice to those who are hurting.

“We still need to have a conversation about what qualifies as the new normal for safety in our schools,” Berg said. “I would hope that our schools could raise our kids to change this.”

Sheldon added: “After a tragedy like this, people will ask why it happened, and a lot of times, we simply don’t have an answer for them. We know it takes time, but we want to feel better right away. You need to be patient, with ourselves and each other.”

Marysville Mayor Jon Nehring has seen the community grow stronger, but he urged people not to leave behind those whose healing is taking more time.

“This tragedy took lives that can never be replaced, but we can move forward,” Nehring said.

Josh Webb, director of counseling for Marysville schools, asserted that young people are “naturally resilient,” but acknowledged that such a trauma can compound other stresses in their lives. To that end, the school district has partnered with outside agencies, including Compass Health and Victim Support Services, to provide counseling and connect students with mental health resources.

“Without treatment, they can be susceptible to anxiety, depression and suicide,” Webb said. “If they wait too long to deal with it, they can develop maladaptive behavior.”

Webb echoed Berg’s insistence that schools must look after their students’ social and emotional well-being as much as their academic performance.

“These are the best kids in the world,” Webb said. “They’re my heroes. They want to keep coming to school.”

Rochelle Lubbers, recovery manager for the Tulalip Tribes, has made it her mission to identify the areas of the community where trauma persists. She’s even received the aid of international trauma centers in assessing the community’s needs.

“Of course, the children have been highly impacted, so we’ve trained them in the Rainbow Dance curriculum,” Lubbers said. “This ritual empowers its participants, so that they’re less likely to draw back into themselves. Their homes have changed, the conversations around them have changed, everything has changed.”

Preschool, kindergarten and first-grade students as Quil Ceda and Tulalip Elementary are receiving trauma care measures, and the tribes have hired therapists specializing in trauma.

“Those measures will have the longest impact,” Lubbers said. “We’ll see it in the years to come. We know there are people who might need help and aren’t getting it yet, but it’s there for them.”