First in a two-part series

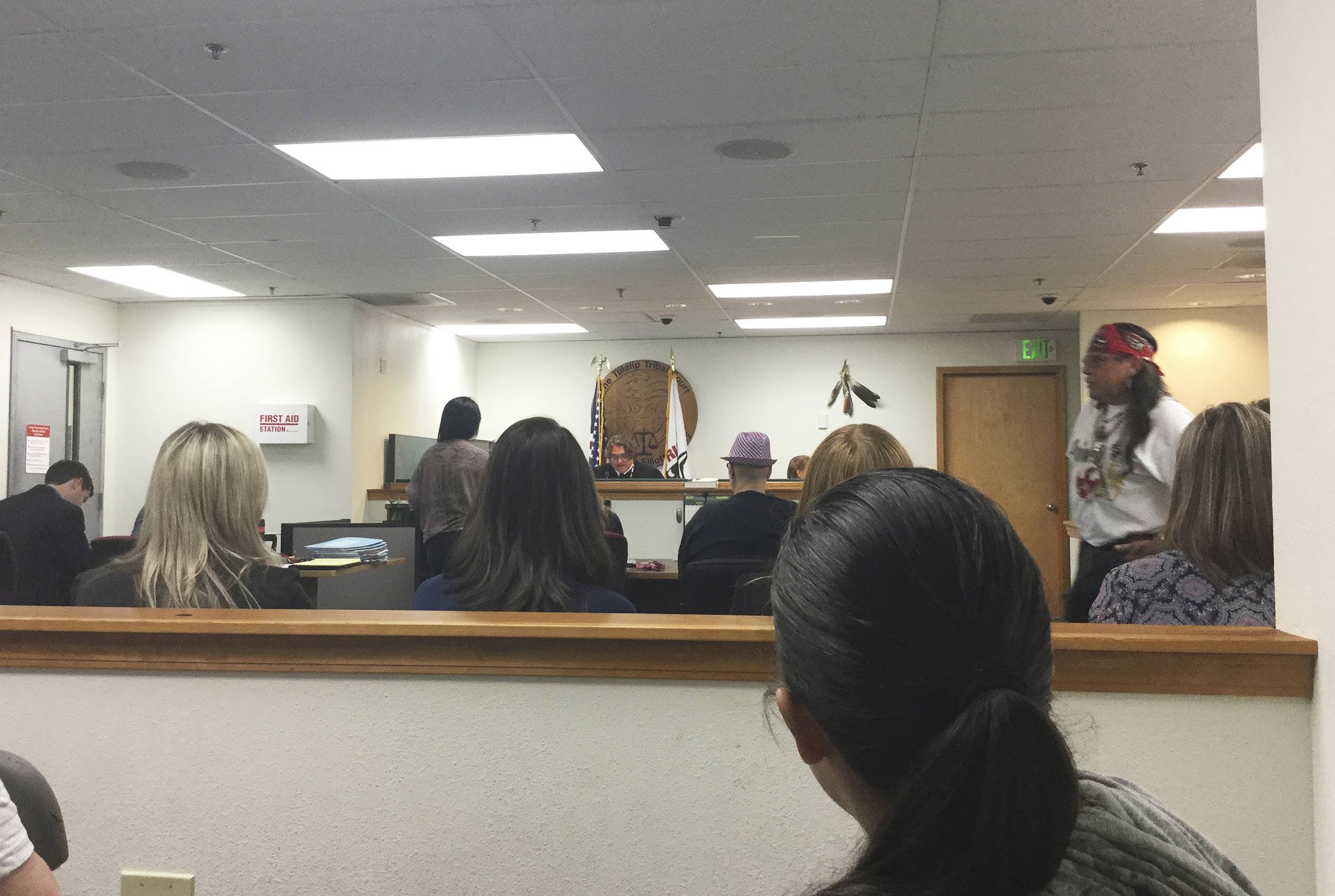

TULALIP – Ron Whitener peruses the afternoon docket on his computer screen in Tulalip Tribal Courtroom 2.

As a tribal court judge, he greets a more-packed-than-usual courtroom that has all the official furnishings of a courtroom, but on this day doesn’t feel much like one.

Ready to proceed, the court administrator announces, “We are going to start with Summerlee Blankenship.”

In the front row, a smiling Blankenship grabs a hug from her supportive grandmother and approaches the bench for a one-on-one conversation with the judge, now familiar with the routine she has done on a weekly basis since January.

Good-naturedly, Whitener says, “You know more about about our programs than we do,” prompting laughter from the gallery.

“How are you?” the judge asked. “Did you have a good week?”

“Yeah, I did.”

“You’ve been at the Healing Lodge,” Whitener said about the Tribes’ transitional home outside Stanwood where she is living along with others seeking a clean-and-sober lifestyle. “How’s that?”

“It’s awesome,” Blankenship answered.

“Everything is going great, and everybody’s talking about how well you’re doing,” the judge said, pausing to look at her most-recent evaluation. “Yeah, you’re having a great week. You’re even doing a little more than you had to.”

“How many days have you been sober?” he asked.

“Sixty days,” said Blankenship, who was met with cheers and applause from onlookers.

Whitener ended, “Not only are you in one hundred percent compliance, but the team is so happy with how well you’re doing that they actually are letting you take from the basket – and you get a water bottle.”

Rewards swag is nice. But it’s no match for the penetrating words of positive reinforcement that can make all the difference in the world for someone addicted to drugs or alcohol trying to heal, sober up and rebuild bridges sometimes burned with family.

Blankenship is one of nine tribal members comprising the inaugural group participating in the Tulalip Healing to Wellness Court.

Their journey through a different kind of diversionary court started nine months ago. With a team of law and justice officials, counselors and peer support in their corner, they are on track to become the court’s first graduating class in the latter half of 2018.

The wellness court is using a team approach for restorative justice, heavily influenced by Native American culture, tribal history and the community’s needs, court officials said. Whitener said the model is much more aligned with the way tribes – through judges and panels of elders – have been resolving disputes for generations by finding ways for offenders to right wrongs and restore balance.

The traditional prosecution approach of jail time, probation and treatment isn’t keeping tribal members from reentering the revolving door of criminal justice as repeat offenders, and doesn’t have much success breaking the cycle of addiction.

The diversion program is “not a magic bullet. With wellness court it doesn’t mean they’re going to make it, but they have a much-better shot,” the judge said.

Wellness Court coordinator Hilary Sotomish said it took a year of planning to get the court started and the framework and requirements in place, along with intensive training through the National Drug Court Institute.

“There have been little things we found that needed to be improved, that we could do better or that we weren’t prepared for yet,” Sotomish said, but the process is running smoothly now.

For non-violent defendants deemed eligible to participate, the life-changing decision is not one to be taken lightly.

“It’s voluntary, so we don’t tell people they have to do it,” Sotomish said. Interested participants are given a two week-trial period to observe whether they want to take part; if they opt out, they are put back on the trial track for eventual sentencing, jail time and fines.

“When they look at the design of the program, most people go for it,” Sotomish said. Then a diversion order is signed. The program is capped at 20 participants, but plans are already under way to expand the program.

The court uses intense supervision, frequent drug testing, drug and alcohol treatment, weekly court visits and tribal cultural treatment activities to assist chronic substances abusers, Sotomish said. After assessment and intake interviews, an individualized treatment plan is tailored for each participant.

Wellness Court is similar to drug courts. It provides structured supervision and rehabilitation for non-violent, repeat drug and alcohol offenders. The average length of the program is 15 months to two years.

By successfully completing the program, participants will have pending charges dismissed and probation cases closed.

For participants, the program rules are strict.

Wellness Court requires weekly court appearances, random urine analysis tests, GPS monitoring, moral reconation therapy, random home and field visits from police, and inpatient and outpatient treatment programs. The program also requires participants to attend three self-help programs such as Alcoholics or Narcotics Anonymous, Sweat Lodge, Red Road to Wellbriety, White Bison, canoeing, dance, pow wows and other cultural activities.

With accountability comes support. The court offers wrap-around services including medical, dental and mental health as needed, chemical dependency treatment, housing, jobs training and placement.

Whitener said the wellness court’s framework opens the door to work on other aspects of the participant’s life. If the addiction is dealt with clinically and housing is covered, more time can be built in to obtain a GED, diploma, or job training, for example. “It’s about getting things out the way that make it hard to achieve,” Whitener said.

“There are a lot of hoops to jump through, and it’s harder than ever now at times, but it’s all doable,” said Blankenship, who is staying at the mansion-converted Healing Lodge, which is owned and operated by the Tulalip Tribes.

While the program provides incentives such as employment and housing assistance, it also remains an entity of the court with the ability to issue sanctions and punishments, including incarceration. Negative behavior such as missed court appearances and drug testing, noncompliance with treatment plans, new criminal charges, violations of court orders and other actions can result in sanctions ranging from reprimands from the judge, apology letter, community service hours, jail and ultimately, termination from the wellness court.

Tribal Prosecutor Brian Kilgore, who served as a defense attorney in Tulalip’s tribal court from 2010 before stepping over to the prosecution side in 2015, understands the differences in roles between the traditional criminal court track and a Wellness Court.

“My number one job is to make sure the community is kept safe, that justice is done, and to hold those responsible accountable for their conduct,” he noted.

That said, the trend toward alternative courts has been gaining traction, and he is a firm believer that the Wellness Court, like drug courts, has the tools and structure to improve lives.

“We’re all trying to see the participant succeed,” Kilgore said. “It’s behavior modification in its most basic form – ‘if I do X, how do they respond?’”

Part two in this series will look at the role family plays in the Wellness Court program.