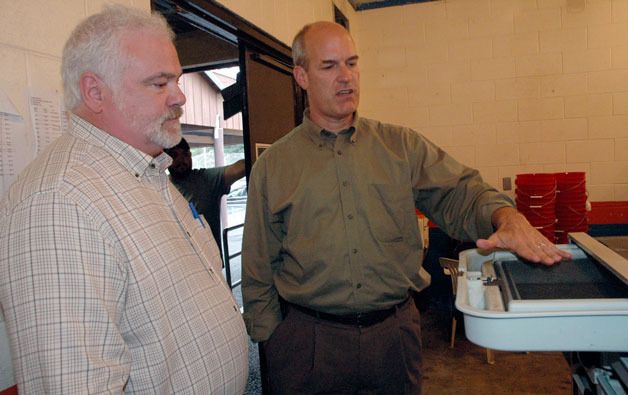

TULALIP — U.S. Rep. Rick Larsen toured through the Tulalip Tribes’ fisheries facilities on the afternoon of Wednesday, Sept. 4, to uphold the legacy of former U.S. Rep. Norm Dicks, who retired this year.

“Norm’s absence left a gap in fish issues for the state, so I decided to learn more about it,” Larsen told the Tulalip Tribal Board of Directors prior to his tour. “Well, it was more that Norm told me last year, ‘You need to learn more about this,’” he laughed.

“We appreciate you stepping up for Norm,” Tulalip Tribal Chair Mel Sheldon Jr. said. “We need more champions.”

While Larsen cited the Tulalip Tribes’ “great body of knowledge” on salmon species and their histories, Sheldon described the history of the Tulalip Tribes’ relationship with salmon as a key aspect of their culture.

“We pay close attention to the waters that drain into Tulalip Bay before they get here,” Tulalip Tribal Board member Glen Gobin said. “It’s so connected to everything we do.”

Tulalip Tribal Board Vice Chair Deborah Parker recalled how her grandmother had to save up airfare to make the trip to defend the Tribes’ treaty fishing rights, and while she herself does not fish, she cherishes salmon as one of the Tribes’ traditional foods.

“The Tribes didn’t have any money back then, but she spent the money for a plane ticket to protect our salmon,” Parker said. “As a mother myself, I enjoy having salmon on my table, and having it as part of our winter ceremonies. It’s important that we remember where we came from, because our Tribal leaders put forth a lot of energy to get us here.”

Terry Williams, the fisheries and natural resources commissioner for the Tulalip Tribes, reported that the level of fish recovery that should be yielded by the past seven years and $50 million of fish programs is being largely canceled out by the pace of development.

“So many of the laws are either not harmonized or are in opposition to one another,” Williams said. “One might say that these fish shall be protected, while another might make it optional. Our treaties are at risk.”

Williams explained that the Tulalip and other Native American tribes are building alliances to get the state Legislature to harmonize its language, while Snohomish Basin Capital Program Coordinator Morgan Ruff pointed out to Larsen that half of Puget Sound’s 14 watersheds fall under his purview.

“The state is investing $100 million in salmon recovery this year, with $5 million of it going toward Snohomish Basin projects including the Qwuloolt Estuary and Smith Island,” Ruff said. “That’s a substantial investment by the state, so we’d like to see it matched by the federal government. We need to continue to advance, rather than just holding our ground.”

Ruff and Williams’ calls for more monitoring were joined by those of Kurt Nelson, environmental division manager for the Tulalip Tribes, and salmonoid enhancement scientist Michael Crewson.

“We need money to support the infrastructure to make these projects happen,” Ruff said.

“The environment has changed so rapidly that we don’t just need more monitoring, but new monitoring systems,” Williams said.

“Before Qwuloolt, we’d done 40 years of habitat restoration, but without the proper monitoring, we had no idea how effective any of it was,” Nelson said. “We need to direct our monies based on what works and what doesn’t.”

Ray Fryberg Sr., fish and wildlife director for the Tulalip Tribes, asserted the impacts of not only global warming and a lack of enforcement on the Tribes’ efforts to rebuild their salmon stocks, but also held seals and sea lions accountable for eating half their brood stock before they can even make it to the Columbia Rover.

“We have a federally protected marine mammal eating up one of our endangered species,” Fryberg said. “I know nobody wants to say that we need to cull those seals, but they don’t migrate anymore, and as opposed to the Endangered Species Act, once a marine mammal receives federally protected status, it never comes off.”