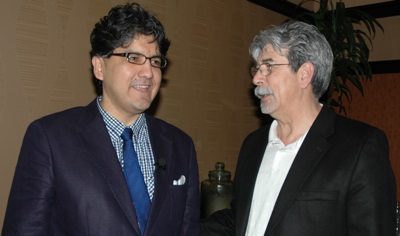

TULALIP — Native American author and filmmaker Sherman Alexie couldn’t get over how far Indian people have come when he visited the Tulalip Tribes.

“It’s so fancy it’s hilarious,” Alexie said March 29 in the Orca Ballroom of the Tulalip Resort Hotel and Casino. “You have an outlet mall on your reservation. My sons have never seen an Indian take a sip of alcohol. It was different being an Indian when I was growing up.”

The Tulalip campus of the Northwest Indian College hosted Alexie’s speaking appearance, part of the first in what they plan to make an annual “Tulalip Reads for Unity” program. Copies of Alexie’s novel, “The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian,” were distributed to Tribal members who made it the subject of book clubs before Alexie’s visit. During his engagement at the Tulalip resort, Alexie recounted his own childhood on the Spokane Indian Reservation, which served as the basis for the life story of his novel’s protagonist.

Alexie was born in 1966 with an excess of spinal fluid on the brain, which went undiagnosed until a playground accident sent him to the emergency room.

“My doctor was a Greek Muslim,” Alexie said. “I was multicultural before it was cool.”

Alexie continued to draw laughter from the crowd as he recalled the physical awkwardness of having an oversized head, hands and feet on a skinny childhood frame, as well as coping with profound vision problems and having 42 teeth in his mouth when medical care on the reservation was severely limited.

“I see these people now, wearing these thick glasses like what I wore from Indian Health Services,” Alexie said. “You think you look stylish, but I think you look poor,” he laughed.

Alexie made light of the extreme poverty in which he grew up, when many of his meals were “commodities,” including powdered milk that he noted would often turn into “nuggets” and canned meat that didn’t even identify which animal the meat came from. His house had no running water until he turned 7 years old, which meant that going to the bathroom required a trip to an outhouse infested with black widow spiders.

“You could either fill the outhouse with bug spray and sit in a cloud of poison, or make surgical strike spray, which meant sticking your head under the rim of the toilet where they would hide,” Alexie said. “People wonder why Indians are angry. It’s not the broken treaties, it’s sticking your head in the toilet in an outhouse,” he laughed.

Alexie turned serious when he explained that he made the decision to leave his reservation’s school when he opened up his math textbook and saw his mother’s maiden name there. It took him a year after he’d told his parents, and everyone else on the reservation, before he finally began attending Reardon, whose academic program he described as “legendary,” but whose majority-white student population intimidated him.

“Those kids were so white they were translucent,” Alexie said. “I found out later, though, that they were scared of me. They actually thought I was going to pull out a bow and arrow to shoot them, from the back pocket of my blue jeans, I guess.”

Alexie gained greater social acceptance when he began to travel the world as an adult, since “as Indians, we’re ambiguously ethnic, so everyone who sees us thinks we’re half of what they are and gives us the indigenous head-nod. In places like New York, you can give yourself whiplash that way.” Since the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, however, the flip side of this is that Alexie has found himself much more likely to be searched by security at airports.

“You can tell an Indian by his rez accent, because at one time in his life, every Indian west of the Mississippi has talked with that accent, that sounds like a combination of Irish and Canadian,” said Alexie, who added that his sons are old enough that they’ve seen his movie, “Smoke Signals,” and now they quote the characters, complete with reservation accents, saying, “Hey, Vic-tor.”

“When I went to Reardon, I realized that street was my ocean and that school was my Ellis Island,” Alexie said. “I was like a first-generation immigrant, even though I was indigenous, which was ironic, which means I was an ironic indigenous immigrant.”

Alexie urged his fellow “indigenous immigrants” to embrace both the culture that they’ve come from and the culture that they’re coming into, without worry about whether their pursuits are sufficiently Indian.

“Whatever you do, you make it Indian just by doing it, so make it good,” Alexie said.